Demand for new pets certainly seemed to spike when the COVID-19 pandemic reached the United States in early 2020 and forced many Americans to spend more time isolated.

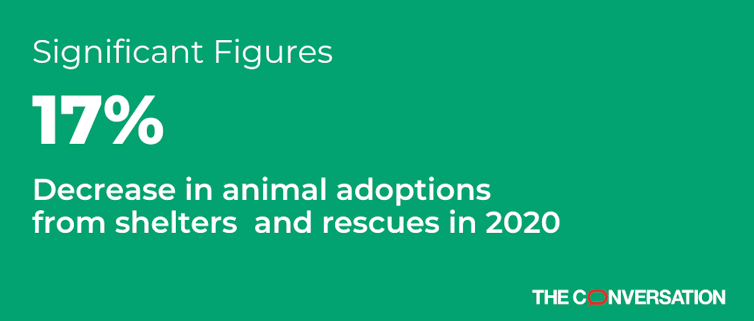

But adoptions from animal shelters and rescues actually fell 17% to approximately 1.6 million in 2020 from over 1.9 million in 2019, according to Shelter Animal Counts, a nonprofit that tracks data regarding animals that spend time in shelters.

How did Americans end up welcoming fewer rescued animals into their homes during the COVID-19 pandemic? The short answer is that there weren’t enough furry friends to go around.

By April 2020, once most Americans began to spend far more time at home than usual, shelters and rescue organizations across the nation had to compile long wait lists because the number of people ready to adopt or foster animals needing new homes already outpaced the number of animals available.

GET THE BARK NEWSLETTER IN YOUR INBOX!

Sign up and get the answers to your questions.

This mismatch between supply and demand occurred partly because 23% fewer pet owners relinquished their companion animals and the number of strays shelter took in fell by 27% in 2020 from 2019.

That doesn’t mean that the total number of pet adoptions from all sources, including breeders, stores and informal networks didn’t rise, as anecdotal reports about strong demand for dog trainers would suggest.

One of the challenges in understanding the bigger picture of animal adoption and puppy purchases is the lack of a central database housing this information. Several organizations track data separately. They use different methods and often don’t make their data easily accessible.

As an anthrozoologist studying human relationships with companion animals, I think people who got new pets had the right idea. Early research results suggest that pets helped people deal with the anxieties resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent lockdowns.

People dealing with depression and anxiety can benefit from spending time with their companion animals by using their pets as proxies for their own personal experiences. For example, they may express concern for their pet on social media as a way of soliciting interpersonal engagement.

In a study I conducted with a colleague at UNLV, we found that most people agreed with statements such as “I tell more stories from my pet’s perspective on social media” and “I am sharing more posts about my pet on social media than before.”

While all people may get some protection against feelings of social isolation from having dogs and cats in their homes, people without children may benefit the most.

Nearly 91% of the people without children who we surveyed answered yes when asked: “Do you feel your pet helped you or is helping you cope with shelter in place?” Comparatively, around 82% of those with children answered yes.

For couples and single people without children, feeding and grooming pets, maintaining routines and – for dog owners – walking regularly can contribute to the consistent schedules that make it easier to stay focused, organized and productive. A study in Australia found that having to walk your dog can keep you more active anytime, including during lockdowns.

[Explore the intersection of faith, politics, arts and culture. Sign up for This Week in Religion.]